Last year, as every bibliophile inevitably does, I came across a book in a bookstore that surprised me on account of the completely unexpected nature of its contents. And like many bibliophiles that come across a book that is more than $30 I hesitated for a while before I finally bought it. The book in question was “50 secrets of magic craftsmanship”, the little-known Art manual of Salvador Dali.

Salvador Dali, as most should know, was the eccentric genius who did much to advance the cause of Surrealist art with his masterful oil-paintings, as well as shock and offend as many people as possible both within and outside the world of Art. However, it is less well known that apart from painting he wrote as well, his bibliography is composed mostly of autobiographies and essays. Make no mistake though, he is not one of those people who appear less spectacular in writing, as he is just as surprising and entertaining an author as he is an artist and celebrity. Though this work is only 192 pages divided into 5 chapters it is a dense jungle of passionate and ornate prose, enlivened and decorated with many sketches done in ink, along with the occasional plate of full-colour reproductions of a few paintings. Nearly every page of this book has at least one drawing in its margins. This makes it moderately difficult to read through quickly or really grasp in one sitting, not that you would want to do such a thing with this work, it being that kind of book you take your time to linger over, laughing and pondering over some absurd yet obscure remark or contemplating some ornate surrealist sketch of a suit of Knight’s armour covered in sea-urchins.

That being said, this is not some coffee-table book full of funny jokes and cartoons to whittle away the hours. It is, exactly as the title suggests, a book of secrets to excelling in the craft of Art, or to be more precise, the style of Oil-painting that Dali used to create many of his most famous artworks. It is also not entirely poetic license which made him use the word “magic” in the title, for as I shall soon explain this book could easily be described as “The Picatrix of the Surrealists”, for many of its “secrets” do have an occult element to them.

The “secrets”, each given a number and occasionally a title, are essentially just tips and practices Dali suggests an artist should follow if they want to excel as an artist. They fall roughly into 3 categories. Firstly, there are the kind of suggestions you expect from an art manual such as advice on choosing which paint to use and what brush to use for each stage of oil-painting. Secondly, there are the more interesting tips of the trade that he has come up with, unique and creative suggestions such as using spider-silk to attach little paper hoods over any freshly painted area of the canvas to stop dust settling on the wet paint as it dries (He is as fascinated by spiders as he is by Sea-urchins and mentions quite a few other uses for spider-silk in this book). Thirdly, in the more eccentric category, are practices and suggestions that can only be called occult, or at least focused more on the psychological, subtle and spiritual aspects of being a good artist, and of making art. Some are fairly well known, but others are so unique that it is clear Dali invented them. An example of the former is the well-known practice of inducing an “alpha state” by sitting in a chair with a key held in one hand over a metal dish so that it falls and wakes you up as you enter the state between wakefulness and sleep, a state of mind that is uniquely creative. He includes an extract from a book of natural magic by J. B. De Porta, since according to Dali some knowledge of it is helpful in choosing subjects for painting, since according to him animals and plants that have a harmonious correspondence with each other, according to the lore of natural magic, will look better together compared to ones traditionally considered unharmonious. He also includes recipes and advice of his own invention that seem very close to what you would find in books of natural or folk magic, such as the “Secret number 41, The wasp medium”, in which one of the ingredients for the oil-based medium he suggests for underpainting is Aspic oil in which amber is dissolved, and which has had three dead wasps soaking in it while exposed to sunlight. Dali apparently discovered by accident that some influence from the wasp gives the medium “…a quality which I had never before experienced, in the ductility, which was honey-like, and in the homogenous fusion of colours.” So, as you can see, practices of this latter variety can be quite eccentric and sometimes difficult to explain easily, but I shall give some more detailed examples from both categories, so you have a better idea of what to expect from this book.

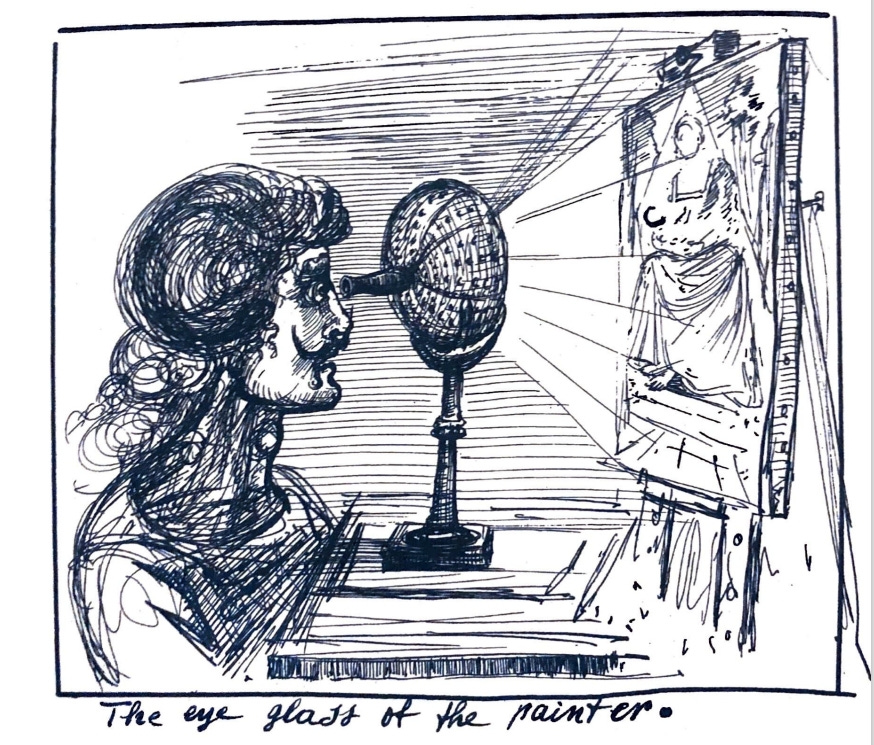

The “eye glass”, or Secret number 11, is a tool for aiding the painter discern whether his painting is as finally finished or needs more work to make it perfect. You get the shell of a sea-urchin, one as large as possible, and use wax to attach a concave crystal lens to its mouth-opening, (or “Aristotle’s lantern” as it is more poetically referred to) followed by using spider-silk to divide the lens into five parts using the vertices of the sea-urchins pentagonal shaped mouth. Directly opposite the mouth drill a hole drill a hole and insert a small magnifying glass (I assume he means something like a telescope, based on his sketch. It would need to be quite small and light to ensure that the Sea-urchin’s shell will not break.) Now, according to Dali, if you look inside through this hole you will see “the interior of one of the most beautiful natural cupolas which it is given to a human creature to contemplate…which I might compare to the Pantheon in Rome”. He then asks that you look upon the painting through this device, and if your painting seems perfect while seemingly surrounded and compressed by the beautiful interior of the Sea-urchin, then it truly is so. I assume that some combination of sacred geometry, natural magic and aesthetics inspired this invention.

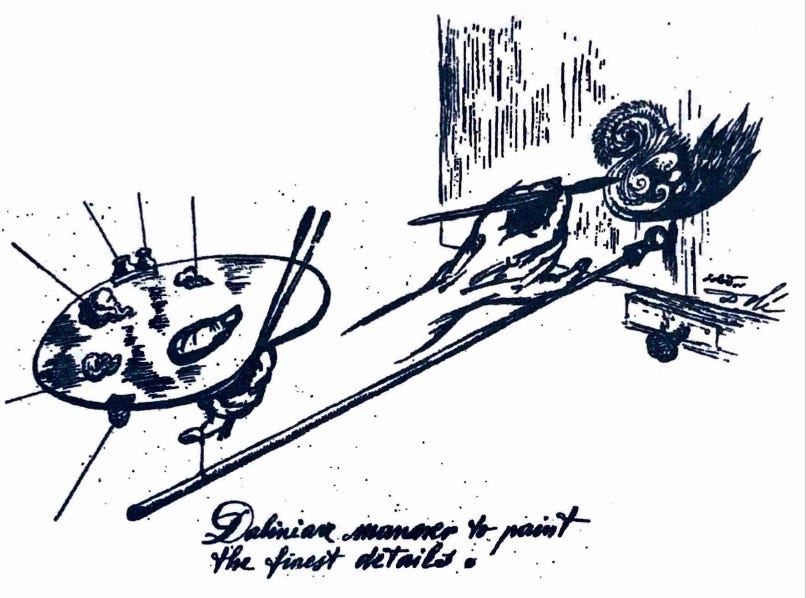

The Manipulation of the Maulstick, or secret number 29, is essentially a better method of using a maulstick according to the experimentations of Dali. Firstly, you must make your Maulstick out of a twig of Elder due to its lightness and flexibility. Secondly, use pitch to attach one end of it to your “Achilles callosity”, this being the term he uses for the callous a painter develops on the last joint of his right little finger, caused by prolonged use of a maulstick. This ensures that this end follows your hand perfectly. Thirdly, suspend the other end of the maulstick with cotton string attached to your left little finger. This will help minimise jerky movements derived from your hands.

As you can see from a mere 2/50th of his “Secrets”, Dali has certainly applied much eccentric genius to the perfection of Art. The question of whether Dali was being completely serious in many of his more unusual suggestions, or whether he deliberately presented them in as bizarre a manner as possible to attract, confuse and repel the reader is something that I am not prepared to answer, for it is something very hard to discern when dealing with someone as eccentric and provocative as Dali. So, I leave these questions to Scholars with a better acquaintance with his work and life. I am also uncertain whether anyone has actually used many of Dali’s more eccentric techniques, both the ones I have just described and the ones I have not, such as the Aranearium or the Sleep with three sea-perch eyes, but I am certain someone has tried them, as I can’t imagine that the advice of someone as important in Art as Dali would be completely ignored, but as far as I am aware only “Secret number 3, or Slumber with a key”, has been explored in any great depth1, and he admits it was not his own invention, but that of Capuchin monks in Toledo. I think therefore that there is much that could be gained from experimenting with these various “Secrets” for those with the artistic skill and open-mindedness to try them. I may consider doing so myself, but as I am not a painter, or really an artist, I feel that I would be unable to accomplish much, to get the most out of them, as many of his suggestions assume some pre-existing skill in painting. If there is anyone reading this essay who is an Artist, especially a painter, I ask that you consider buying or borrowing this book and giving a few of Dali’s practices a go and then talk about your experiences with the rest of the Artist-community. It just does not seem right that this book, a manual by the one of the 20th centuries’ greatest painters, should be as obscure as it is.

Salvador Dali's Creative Secret Is Backed by Science | Scientific American

For those who'd like to see the book: https://archive.org/details/50secretsofmagic0000dali/mode/2up

It's free to sign up and "borrow" the book for an hour at a time.

Absolutely fascinating! I wasn't aware of this book, but just put it on hold. I do like making collages, so I wonder if any of the advice might pertain. I love the idea of using tables of natural magic correspondences to create harmonious visual imagery. That makes quite a bit of sense to me.